One in every 20 children has a vision problem that could lead to permanent vision loss-if it’s not caught early. That’s not a small number. It’s pediatric vision screening that turns a silent, unnoticed issue into something fixable. And the window to fix it? It closes fast.

Why Screen Before Age 5?

The human eye doesn’t fully develop until around age 7. After that, the brain stops adapting to blurry or misaligned images. If a child has lazy eye (amblyopia) or crossed eyes (strabismus) and no one notices, the brain starts ignoring the weaker eye. By age 8, treatment becomes much harder. Studies show that when amblyopia is found before age 5, 80-95% of kids regain normal vision with treatment. After age 8? That number drops to 10-50%.This isn’t theoretical. The Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) study tracked over 5,000 children and proved that early screening saves sight. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force all agree: screening between ages 3 and 5 isn’t optional. It’s essential.

What Gets Screened?

Not all vision problems are the same. The big three targets of pediatric screening are:- Amblyopia (lazy eye): One eye doesn’t develop proper vision because the brain ignores it.

- Strabismus (misaligned eyes): Eyes point in different directions, which can cause double vision or suppression.

- Refractive errors: Severe nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism that’s strong enough to disrupt normal development.

These conditions don’t always show obvious signs. A child won’t say, “I can’t see well.” They’ll just sit closer to the TV, squint, or tilt their head. Parents often assume it’s normal. It’s not.

How Screening Works by Age

Screening isn’t one-size-fits-all. Methods change as kids grow.Newborn to 6 months: The red reflex test is used. A doctor shines a light into each eye. A healthy eye reflects a red glow. If one eye looks white, gray, or dark, it could mean cataracts, retinoblastoma, or other serious issues. This test takes seconds but can catch life-threatening conditions early.

6 months to 3 years: Doctors check eye alignment, pupil response, and movement. They look for nystagmus (jerky eye movements) or constant eye turning. No charts yet-just observation and basic tools.

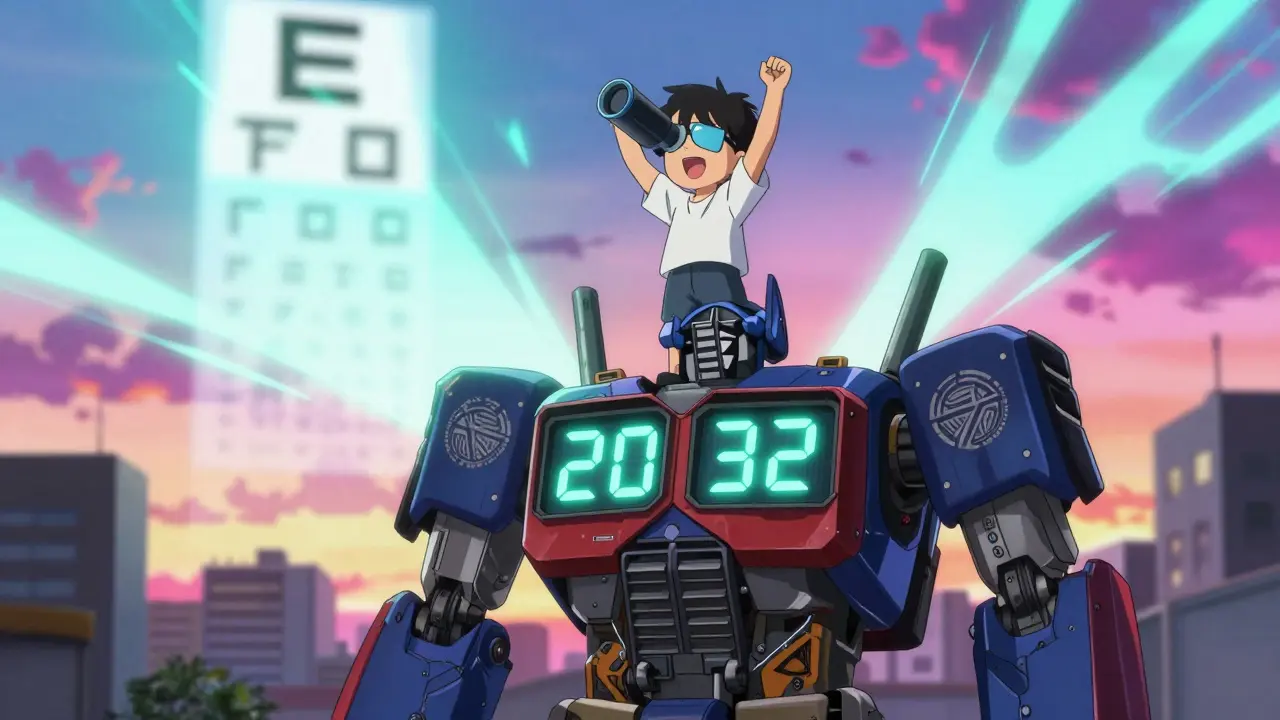

Age 3 and up: This is where visual acuity testing begins. Kids are asked to identify symbols or letters from 10 feet away. For young kids, it’s not letters-it’s shapes like circles, squares, or apples (LEA symbols) or the letters H, O, T, V (HOTV). At age 3, they need to get most of the 20/50 line right. At age 4, it’s 20/40. By age 5, they should read the 20/32 line.

Each eye is tested separately. Covering one eye at a time reveals problems the child might be hiding. If they can’t identify the symbols, they’re referred to an eye specialist.

Old-School Charts vs. High-Tech Devices

There are two main ways to screen: traditional charts and instrument-based devices.Optotype-based screening (charts) is the gold standard for kids who can cooperate. But it’s not perfect. About 1 in 5 three-year-olds won’t cooperate, no matter how much you coax them. Lighting matters. Distance matters. If the chart isn’t at eye level or the room is too dim, results are wrong.

Instrument-based screening uses devices like the SureSight, Power Refractor, or blinq™ scanner. These are handheld, take 1-2 minutes, and don’t need the child to say anything. They measure how light reflects off the retina to detect refractive errors and misalignment. The blinq™ scanner, FDA-cleared in 2018, caught 100% of kids with referral-worthy issues in one study and had 91% accuracy in ruling out healthy eyes.

Here’s the catch: instruments can flag kids who don’t actually need help. A small amount of farsightedness is normal in toddlers. But if the device says “refer,” the child still goes to the specialist. That’s better than missing a real problem.

Most experts now say: use instrument-based screening for kids aged 1-4, and switch to chart-based testing once they’re reliable at age 5. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends starting instrument screening as early as age 1.

Who Does the Screening?

It’s not just eye doctors. Pediatricians, nurses, school staff, and even trained childcare workers can do screening. Training takes just 2-4 hours. The National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health offers free online modules used by over 15,000 providers.But it’s not happening everywhere. A 2018 study found that 25% of screenings had poor lighting. 20% had the wrong distance. In some areas, kids aren’t screened at all because providers don’t have the tools or training. That’s why state laws matter. Thirty-eight states require vision screening before kindergarten. But standards vary. Some use outdated methods. Others don’t require follow-up.

What Happens After a Positive Screen?

A failed screen doesn’t mean the child is blind. It means they need a full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or optometrist. That exam checks for:- Corrective lenses

- Patching the stronger eye to strengthen the weaker one

- Eye muscle surgery for strabismus

- Medication (atropine drops) to blur the good eye temporarily

Treatment often works fast. A child wearing a patch for a few hours a day can see improvement in weeks. Glasses can make a huge difference in just a month. The key is acting before the brain shuts down the weak eye for good.

Why This Matters Beyond Sight

Poor vision affects more than reading. It affects learning, sports, social development, and even self-esteem. Kids with untreated amblyopia are more likely to struggle in school. They may be labeled “lazy” or “not paying attention.”The economic impact is huge. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found that every dollar spent on pediatric vision screening saves $3.70 in lifetime costs-medical care, special education, lost productivity. That’s $1.2 billion saved each year just in the U.S.

What’s Changing Now?

New research is pushing screening earlier. A 2022 JAMA Pediatrics study showed that instrument-based screening works reliably in infants as young as 9 months. The American Academy of Pediatrics is expected to update its guidelines by 2025 to reflect this.Artificial intelligence is now built into devices like blinq™, improving accuracy. And there’s growing focus on equity. Hispanic and Black children are 20-30% less likely to get screened than white children, even when they have the same access to care. That’s a gap that needs closing.

What Parents Should Do

You don’t have to wait for school to notice a problem. If your child:- Squints often or tilts their head to see

- Gets very close to screens or books

- Complains of headaches or eye strain

- Has eyes that don’t track together

- Wants to cover one eye while looking at things

-then get them checked. Even if they passed a school screening, don’t assume it’s enough. Ask your pediatrician: “Did you screen for amblyopia and refractive errors?”

Don’t wait for symptoms. Screening should be part of every well-child visit between ages 3 and 5. If your child is older and has never been screened, it’s not too late. But the sooner, the better.

Tools and Resources

If you’re a provider, the National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health (NCCVEH) offers free training, checklists, and screening kits. For parents, the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s EyeSmart program has simple guides on what to look for.Screening isn’t about finding a flaw. It’s about giving every child a fair chance to see the world clearly. And that’s something no child should miss out on.

Dorine Anthony

December 19, 2025 AT 18:54My niece passed her school screening at 4, but we still took her to the optometrist because she kept squinting during cartoons. Turns out she had a huge refractive error in one eye. Patching for 2 hours a day and now she sees like a hawk. Seriously, don’t wait for symptoms.

Just because the system says ‘passed’ doesn’t mean it’s perfect.

Carolyn Benson

December 21, 2025 AT 12:22They say screening saves sight, but what they don’t tell you is that the entire system is built on the assumption that parents are either rich enough to afford follow-ups or dumb enough to believe the hype.

The ‘$3.70 saved per dollar spent’ statistic? That’s what they use to justify cutting Medicaid benefits later. It’s not prevention-it’s cost-shifting wrapped in a bow made of pediatric optometry brochures.

Aadil Munshi

December 23, 2025 AT 10:02Let’s be real-India’s been doing this since the 90s with handheld autorefractors in rural camps. We didn’t need FDA-cleared gadgets to know a white reflex meant trouble. The real scandal isn’t lack of tech-it’s that the US still treats this like a luxury instead of a public health basic.

And don’t get me started on how ‘instrument-based screening’ is just a fancy way of outsourcing diagnosis to a $500 machine because pediatricians are overworked and underpaid. It’s not innovation-it’s systemic neglect with a UI.

Danielle Stewart

December 24, 2025 AT 23:59As a pediatric nurse, I’ve done hundreds of these screenings. The blinq™ scanner? Game-changer. I’ve had toddlers who wouldn’t look at a chart for a second but would sit still for 90 seconds while the device did its thing.

And yes, it flags false positives-but that’s better than missing a kid who’ll go blind because we were too lazy to push for a referral.

Training takes 2 hours. Do it. Your kid might be one of them.

Erica Vest

December 26, 2025 AT 06:20There is a critical distinction between screening and diagnosis. Screening identifies potential risk; diagnosis confirms pathology. The post correctly emphasizes that a failed screen necessitates a comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation, not immediate intervention.

Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation to initiate instrument-based screening at age one is evidence-based and aligns with longitudinal developmental vision studies published in JAMA Pediatrics (2022).

Parents should not conflate screening failure with visual impairment. It is a red flag-not a diagnosis.

Kinnaird Lynsey

December 27, 2025 AT 03:21I get that early detection matters. But let’s be honest-how many of these ‘screenings’ are just checkboxes on a form? I’ve seen providers rush through it while scrolling on their phones.

And the equity gap? Yeah, it’s real. My cousin’s kid, who’s Black, got flagged twice in school but never got referred because the clinic didn’t have an appointment for six months.

So we’re saving sight… but only if you’re lucky enough to live in a place where someone actually cares.

shivam seo

December 27, 2025 AT 11:42Why are we spending billions on this? Kids used to grow up fine without fancy scanners. My grandpa was blind in one eye from a childhood injury and still built houses for 50 years.

This whole thing feels like another corporate-funded panic to sell more glasses and eye surgery. You’re turning normal childhood behavior into a medical crisis.

Next they’ll be screening for ‘poor focus’ and prescribing ADHD meds for kids who just like to stare at clouds.

Andrew Kelly

December 29, 2025 AT 09:59Who exactly decided that a 3-year-old has to read letters on a chart? This isn’t a test of vision-it’s a test of obedience. The whole system is designed to make parents feel guilty if their kid doesn’t perform.

And now we’re scanning infants? What’s next? DNA screening at birth to predict if they’ll be ‘visionally compliant’ by age 5?

This isn’t medicine. It’s behavioral conditioning dressed up in white coats and FDA stickers.

Anna Sedervay

December 30, 2025 AT 18:12Let’s not pretend this is about children’s health-it’s about controlling parental behavior. The ‘free training’ modules? They’re sponsored by the same conglomerates that manufacture the screening devices. You think the NCCVEH doesn’t have corporate backers?

And why is it always ‘parents should ask’? Because the system wants you to be the one pushing for care, not the providers.

It’s a brilliant scam: make parents feel responsible for a system that refuses to fund it properly.

Also, ‘LEA symbols’? That’s just a rebranding of ‘cartoon shapes’ so it sounds like science.

Ashley Bliss

December 31, 2025 AT 11:02I cried when my daughter got her first pair of glasses at age 4. She’d been sitting so close to the TV, I thought she was just obsessed with cartoons. Turns out, she couldn’t see the faces on the screen.

And then the school nurse said, ‘Oh, we screened her last year-she passed.’

Passed? Passed what? The test? Or the system’s low expectations?

My daughter didn’t fail. The system did. And now she sees the stars for the first time. I’ll never stop screaming about this.

Someone needs to make this mandatory in every pediatric visit. Not ‘recommended.’ Mandatory. Like vaccines.

And if you’re not doing it, you’re not a good parent-you’re just blind to the truth.

Meenakshi Jaiswal

January 2, 2026 AT 05:20In rural India, we use smartphone-based autorefractors now-cheap, portable, and accurate. One nurse can screen 50 kids in a day. No need for fancy machines or 2-hour training.

The real issue isn’t tech-it’s access. If a child in a village in Bihar can get screened, why is a kid in rural Mississippi waiting months?

It’s not about tools. It’s about will.

Mahammad Muradov

January 3, 2026 AT 08:09Everyone’s talking about screening, but nobody talks about the fact that 40% of kids who get referred never see a specialist. Insurance denies it. Parents don’t have time. Or worse-they’re told, ‘It’s not serious.’

So we screen, we flag, we refer… and then we do nothing.

That’s not prevention. That’s performance.