Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological disorder-it’s an internal betrayal. Your own immune system, designed to protect you, turns against the very core of your nervous system. It targets the myelin sheath, the fatty insulation that wraps around nerve fibers like plastic on a wire. When that insulation gets stripped away, signals between your brain and body start to short-circuit. That’s when numbness hits, vision blurs, or your legs refuse to carry you. And it’s not random. This is a targeted, ongoing attack-engineered by your immune cells, fueled by genetics, and triggered by things like viruses, low vitamin D, or smoking.

What Happens When Your Immune System Goes Rogue

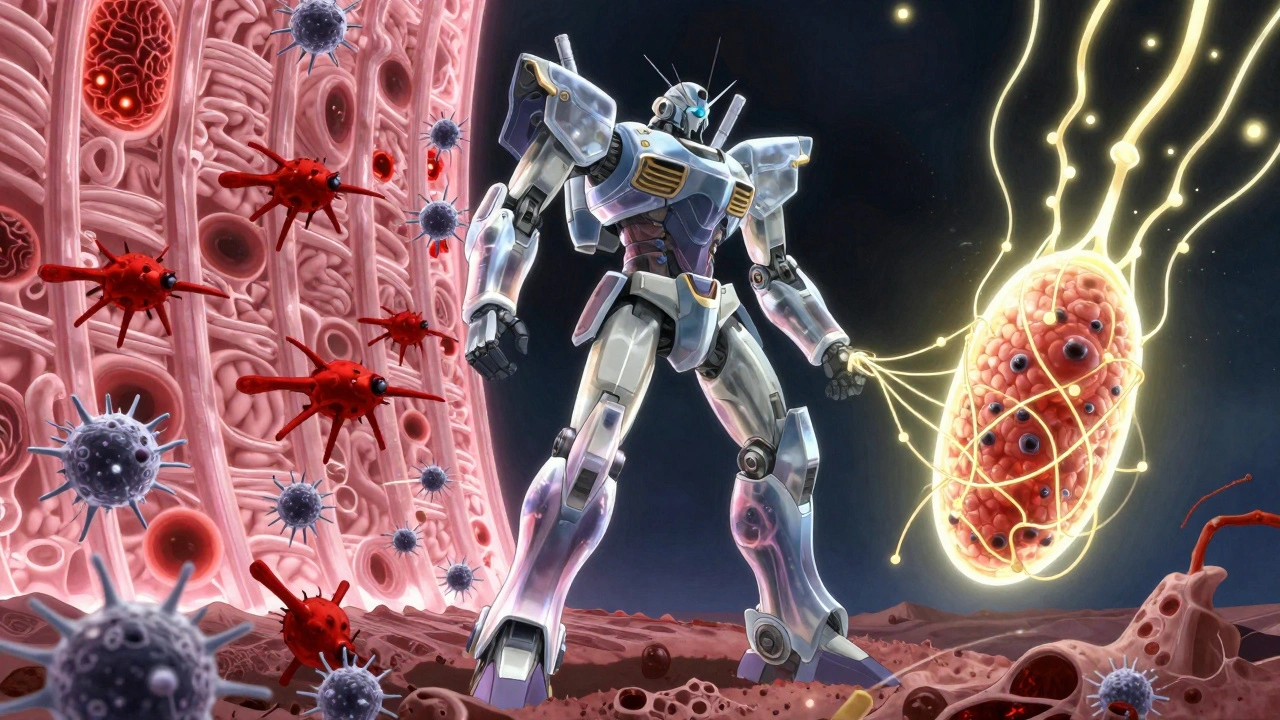

The central nervous system-your brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves-is usually off-limits to immune cells. A tight barrier called the blood-brain barrier keeps them out. But in multiple sclerosis, something breaks that wall. CD4+ T cells, especially a dangerous subset called Th17 cells, get activated by myelin proteins they’re not supposed to recognize. These cells cross into the CNS, sounding the alarm. Then come the B cells, macrophages, and microglia. Together, they form a hostile environment. They don’t just attack myelin-they choke off the brain’s ability to repair it.Think of myelin like the rubber coating on electrical wires. Without it, nerve signals slow down or disappear. That’s why people with MS feel tingling, weakness, or sudden vision loss. The damage shows up as lesions-scarred patches where myelin has been destroyed. These aren’t just random spots. In relapsing-remitting MS, the most common form, these lesions flare up during attacks, then partially heal. But each attack leaves behind some damage. Over time, the nerves themselves start to degenerate. That’s when disability becomes permanent.

The Real Culprits Behind the Attack

It’s not just one thing that causes MS. It’s a perfect storm. First, you need the right genes. Certain HLA variants make you more likely to develop it. But genes alone aren’t enough. Environmental triggers push the button. One of the biggest? Epstein-Barr virus. People who’ve had mono are 32 times more likely to get MS. That’s not a coincidence. The virus tricks the immune system into cross-reacting with myelin proteins.Vitamin D deficiency plays a major role too. People living farther from the equator-like in Canada, Scandinavia, or southern Australia-have higher MS rates. Low sun exposure means lower vitamin D, which helps regulate immune responses. Studies show people with levels below 50 nmol/L have a 60% higher risk. Smoking? It doesn’t just hurt your lungs. It makes MS worse, increasing the chance of progression by 80%. Even secondhand smoke raises the risk.

And then there’s gender. Women are 3.2 times more likely to get MS than men. Why? Hormones, immune system differences, and maybe even how women’s immune cells respond to Epstein-Barr. We don’t have all the answers, but the pattern is clear: it’s not just bad luck. It’s biology meeting environment.

What Symptoms Tell You About the Damage

Symptoms vary wildly because the lesions can pop up anywhere in the CNS. But some show up again and again. Fatigue hits 80% of people with MS-not the kind you get from a long day, but a crushing, bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t go away with rest. Numbness or tingling in limbs? That’s demyelination in the spinal cord or brainstem. Vision problems? Optic neuritis, where the optic nerve gets inflamed. It can blur vision, cause pain with eye movement, or even lead to temporary blindness in one eye.Then there’s Lhermitte’s sign-the electric shock feeling that runs down your spine when you bend your neck. It happens because demyelinated nerves in the cervical spine fire abnormally. Walking becomes hard when signals from your brain can’t reach your legs properly. Bladder issues? That’s the brain losing control over the nerves that manage urination. These aren’t just annoyances. They’re direct results of your immune system’s destruction of myelin.

How Treatments Fight Back

We can’t yet stop MS completely, but we can slow it down. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) target the immune system’s worst actors. Ocrelizumab, for example, wipes out CD20+ B cells-the ones producing harmful antibodies and inflammatory signals. In clinical trials, it cut relapses by 46% and slowed disability in primary progressive MS by 24%. Natalizumab blocks immune cells from crossing the blood-brain barrier. It’s powerful-reducing relapses by 68%-but comes with a rare but deadly risk: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a brain infection caused by a dormant virus reactivating.Newer drugs are more precise. Siponimod and cladribine target specific immune pathways without wiping out entire cell populations. And then there’s the hope of repair. Clemastine fumarate, originally an antihistamine, showed in trials that it could improve nerve signal speed by 35%-hinting that remyelination might be possible. Researchers are now testing drugs that wake up oligodendrocytes, the brain’s myelin-producing cells, to rebuild damaged insulation.

What’s on the Horizon

The future of MS treatment isn’t just about suppressing the immune system-it’s about fixing the damage. Scientists have found that neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), sticky webs of DNA and toxins released by immune cells, help break down the blood-brain barrier. In 78% of acute MS relapses, these NETs are elevated. Blocking them could prevent attacks before they start.Another breakthrough? Dendritic cells in the brain are now known to actively present myelin to T cells, keeping the attack going. Targeting these cells could shut down the cycle at its source. Blood tests measuring neurofilament light chain (sNfL) are becoming standard. Levels above 15 pg/mL mean active inflammation is happening-even if you feel fine. That lets doctors adjust treatment before damage piles up.

And the big picture? MS isn’t one disease. It’s at least four different patterns of damage, each with its own immune signature. That’s why personalized medicine is the next frontier. One person’s MS might be driven by B cells. Another’s by T cells. Another’s by chronic microglia activation. Tailoring treatment to the individual’s immune fingerprint will be the key to stopping progression.

Living With MS Today

The outlook has changed dramatically. Twenty years ago, half of people with relapsing-remitting MS needed a cane or walker within 15 to 20 years. Today, with early treatment, that number is down to about 30%. Many people live full, active lives. Exercise, stress management, and avoiding smoking make a real difference. Physical therapy helps maintain mobility. Cognitive rehab supports memory and focus. And support networks-like online communities where people share stories of optic neuritis attacks or Lhermitte’s sign-help reduce isolation.MS isn’t a death sentence. It’s a lifelong condition that requires vigilance, but it doesn’t have to define you. The immune system may have turned traitor, but science is learning how to outsmart it-one discovery at a time.

Is multiple sclerosis caused by a virus?

Not directly, but Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the virus that causes mononucleosis, is the strongest known environmental trigger. People who’ve had EBV are 32 times more likely to develop MS. The virus doesn’t cause MS by itself, but it likely tricks the immune system into attacking myelin because of molecular similarities between viral proteins and myelin proteins.

Can you reverse the damage from multiple sclerosis?

Currently, no treatment fully reverses existing damage. But the brain has some ability to repair itself through remyelination. Early-stage clinical trials with drugs like clemastine fumarate have shown improved nerve signal speed, suggesting new myelin can form. Researchers are now testing therapies designed to wake up the brain’s own myelin-producing cells. While full repair isn’t possible yet, slowing further damage and encouraging repair is now a realistic goal.

Why are women more likely to get MS than men?

Women are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop MS, especially in high-prevalence regions. The exact reason isn’t fully known, but it’s likely a mix of hormonal differences, immune system biology, and how female immune cells respond to triggers like Epstein-Barr virus. Estrogen may play a role in immune activation, and X-chromosome genes linked to immune regulation may contribute to higher susceptibility.

Does vitamin D prevent multiple sclerosis?

Vitamin D doesn’t prevent MS outright, but low levels are strongly linked to higher risk. People with serum vitamin D below 50 nmol/L have a 60% increased risk of developing MS. While taking supplements hasn’t been proven to stop MS once it starts, maintaining healthy levels (75-125 nmol/L) is recommended for immune regulation and overall nervous system health.

Can you outgrow multiple sclerosis?

No, MS is a lifelong condition. While symptoms may improve during remission, the underlying immune dysfunction remains. Some people with relapsing-remitting MS eventually transition to secondary progressive MS, where damage accumulates steadily. Early and consistent treatment significantly slows progression, but there’s no cure yet. The goal is to manage the disease so it has minimal impact on daily life.

Olivia Portier

December 7, 2025 AT 05:18just read this whole thing and honestly? i’m crying. not because it’s sad, but because for the first time i feel seen. i’ve had ms for 8 years and no doctor ever explained it like this. the myelin = plastic on a wire analogy? chef’s kiss. thank you.

Tiffany Sowby

December 9, 2025 AT 04:57why do we even bother treating this? it’s just a genetic flaw. we should be spending money on people who didn’t choose to break.

Asset Finance Komrade

December 10, 2025 AT 06:28One must contemplate the ontological implications of immune betrayal. Is the self not the sum of its biological functions? If the immune system-our internal sentinel-turns traitor, does the individual cease to be? Or merely become… a site of conflict? 🤔

Jennifer Blandford

December 11, 2025 AT 06:50OMG I just got diagnosed last month and this post made me feel like maybe… just maybe… I’m not alone. Also, clemastine? That’s the antihistamine from my allergy meds?? I’m gonna google that right now. 💪❤️

Brianna Black

December 13, 2025 AT 05:45As a neurology researcher with over 12 years in clinical trials, I must emphasize the paradigm shift here: we are no longer treating symptoms-we are intercepting immune cascades at their source. The emergence of sNfL as a biomarker is revolutionary. It allows for preemptive intervention, transforming MS from a reactive to a predictive disease.

Shubham Mathur

December 14, 2025 AT 17:32EBV is the real villain here and nobody talks about it enough. I got mono in college and now I have ms. Coincidence? I think not. Also vitamin D is free and sunlight is free and smoking is stupid. Why are we even here?

Stacy Tolbert

December 15, 2025 AT 10:31It’s so unfair. I was just starting to feel normal again. Now this? Again? Why me? I just wanted a normal day.

Ronald Ezamaru

December 16, 2025 AT 19:22My brother has secondary progressive MS. He’s been on ocrelizumab for three years. His relapses dropped from 3 a year to zero. He still has fatigue and numbness, but he walks his dog every morning. That’s victory. Early treatment saves function. Don’t wait.

Ryan Brady

December 17, 2025 AT 03:13So we’re spending billions to fix a disease that mostly affects rich white women? What about real problems? Like inflation or border security? 🤷♂️

Raja Herbal

December 18, 2025 AT 18:34Wow. So we’re blaming Epstein-Barr now? Next they’ll say the moon caused it. My uncle had MS and he never even had mono. But sure. Science.

Iris Carmen

December 19, 2025 AT 19:05i’ve had lhermitte’s sign since 2020 and i still laugh when it happens. like, ‘oh cool, my spine just did a lightning show again.’

Rich Paul

December 19, 2025 AT 22:10Look, the Th17 axis is overrated. Everyone’s focused on B cells and T cells but the real issue is microglial priming via gut dysbiosis. I read a preprint last week-your microbiome’s messing with your HLA-DR expression. No one’s talking about this. Also, probiotics. Try them. I’m not a doctor but I play one on Reddit.

Delaine Kiara

December 20, 2025 AT 04:17Okay, but have you considered that MS is actually a spiritual awakening? The immune system isn’t attacking your nerves-it’s trying to purge your soul of toxic energy. I had a vision during my last relapse. My myelin was a golden rope being rewoven by angels. Also, I’m starting a cult. Call it Remyelination Rising. 🌈✨

Ruth Witte

December 20, 2025 AT 05:06Y’ALL. I started walking 30 mins a day after my diagnosis. I lost 20 lbs. My fatigue is better. My legs don’t feel like concrete. I’m not cured-but I’m fighting. And you can too. 💪🔥 #MSWarrior #NoGivingUp

Noah Raines

December 22, 2025 AT 04:49My neurologist said the same thing about sNfL. I didn’t believe her until my last blood test. 28 pg/mL. I was asymptomatic. That’s wild. Science is scary sometimes.

Olivia Portier

December 23, 2025 AT 10:30to @5745: i get it. you think this is a ‘rich white woman disease.’ but my best friend’s a black man from texas with ms. my cousin’s a mexican immigrant who got diagnosed at 24. this isn’t about privilege. it’s about biology. stop being a jerk.