When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA know it will? The answer lies in bioavailability studies-the quiet, rigorous science behind every generic drug approved in the U.S.

What Bioavailability Really Means

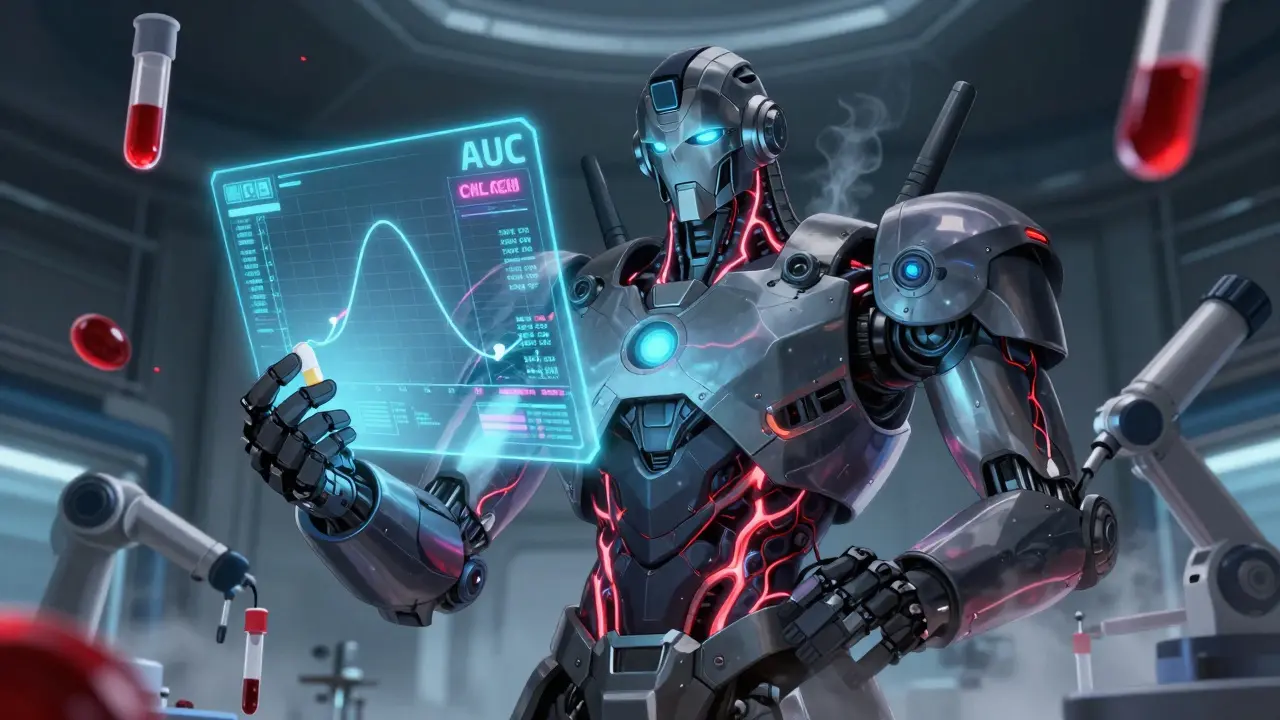

Bioavailability isn’t just about whether a drug gets into your body. It’s about how fast and how much of the active ingredient reaches your bloodstream. For a generic drug to be approved, it must deliver the same amount of medicine at the same rate as the original. That’s measured using two key numbers: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration). AUC tells you the total drug exposure over time. Think of it like how long your body is bathed in the medicine. Cmax shows the highest level the drug reaches in your blood-this tells you how quickly it’s absorbed. If a generic has a lower Cmax, it might take longer to start working. If AUC is lower, you might not get enough of the drug over time. These aren’t theoretical numbers. They’re measured by drawing blood from healthy volunteers at 12 to 18 time points over 24 to 72 hours after they take the pill. Labs then use highly accurate methods to detect tiny amounts of the drug in plasma. The whole process has to meet strict FDA standards: accuracy within 85-115%, precision under 15% variability. No room for error.How Bioequivalence Is Proven

Bioequivalence is the goal. It means the generic and brand-name versions are essentially the same in how your body handles them. The FDA doesn’t require new clinical trials proving the generic treats the same condition. Instead, it relies on pharmacokinetic data. The rule? The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of AUC and Cmax between the generic and brand must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand’s average AUC is 100 units, the generic’s must be between 80 and 125 units to pass. This isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on decades of clinical evidence. A 20% difference in exposure usually doesn’t change how well a drug works-or cause side effects-for most medications. But there are exceptions. For drugs like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine, where even small changes can be dangerous, the range tightens to 90-111%. Studies are typically done as crossover trials: each volunteer takes the brand, waits weeks for it to clear their system (a washout period), then takes the generic. This design controls for individual differences in metabolism. Around 24 to 36 healthy adults are enrolled, selected to minimize variability. Power analysis ensures the study has at least an 80% chance of detecting a meaningful difference.When the Rules Get More Complex

Not all drugs are created equal. Some are tricky. Highly variable drugs-like tacrolimus or certain antidepressants-show big differences in how people absorb them, even when taking the same brand. For these, the FDA allows something called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). Instead of a fixed 80-125% range, the acceptable window widens to 75-133% if within-subject variability exceeds 30%. Then there are complex formulations: extended-release pills, inhalers, gels, patches. A simple AUC and Cmax comparison doesn’t cut it. For an extended-release oxycodone tablet, the FDA requires equivalence at multiple time points-not just peak and total exposure, but how the drug releases over 12 or 24 hours. For topical testosterone gel, they measure skin absorption and hormone levels over days, not just blood concentrations. Some drugs can skip human studies entirely. If they’re BCS Class 1-highly soluble and highly permeable, like atorvastatin or metoprolol-and the generic matches the brand’s ingredients and dissolution profile exactly, the FDA may grant a waiver. This saves time and money without compromising safety.

What Happens When a Generic Fails

It happens more often than most people realize. In one documented case, a generic version of a common antidepressant showed an AUC ratio of 1.16-16% higher than the brand. That sounds good, right? But the upper limit of its 95% confidence interval hit 1.30. That’s outside the 1.25 limit. The product was rejected. Another case showed a 10% lower AUC (0.90 ratio). The company had to reformulate. Maybe they changed the binder, the coating, or the particle size. Small changes matter. A different excipient can slow dissolution. A different manufacturing process can alter how the tablet breaks down in your stomach. These aren’t failures of quality control. They’re failures of design. The generic manufacturer didn’t replicate the original’s behavior. And the FDA won’t approve it until they do.Real-World Impact: Do Generics Really Work?

Critics point to isolated stories: a patient whose seizures returned after switching to a generic antiepileptic, or someone who developed palpitations after switching from brand-name amlodipine to the generic. The Epilepsy Foundation tracked 187 such reports between 2020 and 2023. But FDA reviews found only 12 cases-about 6.4%-could be linked to bioequivalence issues. The rest? Missed doses, stress, other meds, or natural fluctuations in the condition. On the flip side, pharmacists who’ve run hundreds of bioequivalence studies report zero clinical differences when generics pass the tests. One experienced researcher noted: “In 47 studies I’ve conducted, every generic that passed BE criteria performed identically to the reference in simulated patient populations.” The data backs this up. Over 15,000 generic drugs have been approved since 1984. Ninety-seven percent of U.S. prescriptions are now for generics. And yet, only a handful of documented cases show harm tied to bioequivalence limits. The system works-for most people, most of the time.

The Future of Bioequivalence Testing

The field is evolving. The FDA is now using AI to predict bioavailability from formulation data. In a 2023 pilot with MIT, machine learning models predicted AUC ratios for 150 drugs with 87% accuracy. That could cut down the need for human trials for simple generics. In vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) models are also advancing. If a tablet dissolves in a lab test exactly like the brand, and that pattern reliably predicts how it behaves in the body, maybe we won’t need blood draws at all for some drugs. But for now, the gold standard remains blood samples, careful timing, and strict statistical thresholds. The system isn’t perfect. It’s not meant to be. It’s designed to be safe, reproducible, and scalable. And it’s saved patients and the healthcare system billions.Why This Matters to You

If you take a generic, you’re trusting this process. You’re trusting that the FDA didn’t cut corners. That the lab didn’t skip a sample. That the manufacturer didn’t swap a cheap ingredient that changes how the drug behaves. The next time you refill a prescription and see a different pill color or shape, remember: behind that switch is a 6-month study, 30 volunteers, 150 blood draws, and a statistical analysis that says, “This is the same.” It’s not magic. It’s science. And it’s why you can trust your generic meds.What is the difference between bioavailability and bioequivalence?

Bioavailability measures how much and how quickly a drug enters your bloodstream after you take it. Bioequivalence compares two versions of the same drug-usually a generic and the brand-name-to see if they have the same bioavailability. A generic must show bioequivalence to get FDA approval.

Why do some generics have different shapes or colors?

The active ingredient must be identical, but the inactive ingredients-like fillers, dyes, and coatings-can differ. These affect appearance and sometimes how fast the pill dissolves, but not the drug’s effectiveness as long as bioequivalence is proven. The FDA allows these differences to avoid trademark issues with the brand.

Are all generic drugs required to undergo bioavailability studies?

Most are. But for certain simple, highly soluble, and well-absorbed drugs (BCS Class 1), the FDA may waive human studies if the generic matches the brand’s dissolution profile exactly. For complex drugs like extended-release tablets or inhalers, human studies are always required.

Can a generic fail bioequivalence testing even if it has the same active ingredient?

Yes. Two pills can have identical active ingredients but different excipients, particle sizes, or manufacturing processes. These changes can alter how quickly the drug dissolves or is absorbed. A generic can fail if its AUC or Cmax falls outside the 80-125% range compared to the brand.

Why are narrow therapeutic index drugs treated differently?

Drugs like warfarin, lithium, and levothyroxine have a very small margin between an effective dose and a toxic one. Even a 10% difference in blood levels can cause serious side effects. So the FDA tightens the bioequivalence range to 90-111% and sometimes requires additional testing or physician approval before switching.

Sarah Mailloux

January 16, 2026 AT 09:20So many people think generics are just cheap knockoffs but this breakdown shows how insane the testing is. 150 blood draws per study? 30 volunteers? That’s wild. I used to be skeptical until I saw how much science goes into every little pill.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 17, 2026 AT 21:41Ohhh, so THIS is why Indian pharma companies get slapped with warning letters? They think ‘same active ingredient’ = ‘same drug’… and then wonder why the FDA rejects them? LOL. You can’t just swap lactose for starch and call it a day. The system works-unlike your ‘cost-cutting’ shortcuts.

RUTH DE OLIVEIRA ALVES

January 19, 2026 AT 10:40The rigorous methodological standards outlined herein represent a paradigm of regulatory science that prioritizes patient safety over commercial expediency. The statistical thresholds employed-particularly the 80–125% confidence interval-are not arbitrary, but rather empirically validated thresholds grounded in pharmacokinetic principles and decades of clinical observation. It is imperative that public discourse reflects this depth of scientific integrity.

Annie Choi

January 21, 2026 AT 02:54BCS Class 1 waivers? Yes. AI predicting bioavailability? Hell yes. This is the future. We’re moving from blood draws to algorithms-and it’s about time. The FDA’s playing 4D chess while the rest of us are still arguing about pill colors. Let’s trust the data, not the branding.

Arjun Seth

January 23, 2026 AT 01:33They say it’s safe… but what about the people who got sick? You ignore the anecdotes, but those are real lives. You think 97% success rate means anything when your aunt’s seizures came back? The system is rigged for big pharma to profit off cheap pills while patients pay the price.

Dan Mack

January 24, 2026 AT 09:51Wait… so they test this on healthy volunteers? But what if you’re not healthy? What if you’re diabetic? Or have liver damage? They’re not testing on the people who actually take these drugs. This whole thing is a lie. The FDA’s just letting Big Pharma slide. I’ve seen the documents. They’re hiding something.

Amy Vickberg

January 24, 2026 AT 15:44I used to freak out switching generics, but after reading this I feel way better. I didn’t realize how much goes into it. Honestly, I’m glad they’re this strict. My blood pressure meds used to mess me up, but the generic version I’m on now? Perfect. Science wins.

Nishant Garg

January 25, 2026 AT 18:27Back home in Mumbai, we joke that Indian generics are ‘the same but cheaper’-but this? This is the real story. It’s not magic. It’s math, sweat, and blood samples at 3 a.m. in a lab somewhere in Ohio. I used to think it was all about price. Now I see it’s about precision. Respect.

Nicholas Urmaza

January 25, 2026 AT 20:28Let’s be clear: if you’re taking a generic and it works, don’t overthink it. The FDA doesn’t approve junk. The data speaks. Stop listening to fearmongers on social media. This system has saved billions and kept millions alive. Trust the process.

Amy Ehinger

January 26, 2026 AT 18:53I work in a pharmacy and I’ve seen people panic because their generic looks different. I hand them this article every time. It’s wild how much they don’t know. The color change? That’s just to avoid trademark stuff. The science? Still solid. People just need to chill and trust that someone did the math for them.

Tom Doan

January 27, 2026 AT 06:02Interesting that you mention AI predicting bioavailability. But isn’t that just replacing one black box with another? If the model predicts AUC with 87% accuracy, what happens when it’s wrong? Who’s liable? And what about drugs that fall in the 13% margin of error? The FDA still needs human data. Because biology isn’t a spreadsheet.